However, since Coronavirus is impacting every facet of our lives – from school closures and social distancing to quarantines and lockdowns, not to mention job losses and stimulus checks – it is easy to see how the information need is growing in fast and unexpected ways.

As is true for many other topics, search engine query logs may be able to give insight into the information gaps associated with Covid-19. The global reach of the Bing search engine and the amount of time people spend on their devices (especially in quarantine) make the Bing search query logs a potentially valuable source of information about the pandemic which may have insights that can be useful for the public and public health authorities. It is also a very direct way of looking at all the other topics that don’t explicitly reference the crisis, but reflect people’s experience of living through it, such as topics related to the economy, working from home, online education, and home fitness.

Announcing the Bing search dataset for Coronavirus Intent

We are pleased to announce that we have already made Covid-19 query data freely available on GitHub as the Bing search dataset for Coronavirus intent, with scheduled updates every month over the course of the pandemic. This dataset includes explicit Covid-19 search queries containing terms such as corona, coronavirus, and covid, as well as implicit Covid-19 queries that are used to access the same set of web page search results (using the technique of random walks on the click graph). Top-ranked examples in the US show that such implicit queries are crucial for understanding specific concerns – e.g., “hand sanitizer”, “n95 mask”, and “stimulus check for 2020” – in addition to the more general concerns such as “coronavirus update”. To protect user privacy, infrequent queries and queries containing personal data are filtered from the dataset, while raw query counts are replaced by popularity scores between 1 and 100 reflecting normalized query counts for a given day and country.

We have already seen how Covid-19 has elevated the level of data-oriented discussion, with daily updates in Covid-19 statistics (e.g., tests conducted, confirmed cases), as well as projections estimated by epidemiological and machine learning models, all communicated using data visualizations such as bar charts, line charts, and choropleth maps. The dataset itself also shows a growing public demand for interactive visualizations of trusted data sources; for example, “coronavirus map” queries peaked on March 11, “johns hopkins coronavirus map” queries peaked on April 2, and “johns hopkins coronavirus dashboard” queries peaked on April 6. Not only can our dataset provide inputs to machine learning models aiming to draw on population search behaviour as a signal, it can also provide a new data source for the trusted Covid-19 dashboards already in use, as well as powering entirely new interactive experiences based on use of search data to map the what, when, and where of population-level Covid-19 concerns.

In each of these cases, the data science community plays the crucial role of translating raw data tables into practical data tools for Covid-19 response efforts. We are already seeing examples of the Bing search dataset for Coronavirus intent being discovered and used by members of the community. In particular, it has been featured on the deeplearning.ai blog of the company run by Professor Andrew Ng, used for exploratory visual analysis in Python and R, and included as a data science resource by the Academic Data Science Alliance and Coronavirus Tech Handbook. In the rest of this blog post, we share how our data scientists are using Power BI to create interactive dashboards to this dataset and transform our understanding of the unfolding crisis.

Discovering insights in the Bing Covid-19 dataset

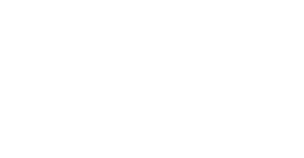

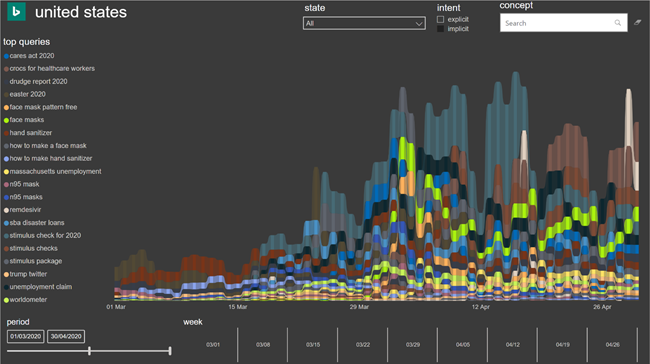

One of the fastest ways to begin exploring the dataset is through the use of interactive visualizations, such as in dashboards created using the freely-available Power BI Desktop. Here is an example page from a Power BI report we created to visualize and explore the Bing search dataset for Coronavirus intent, showing the count of unique US-based queries each week from January to April:

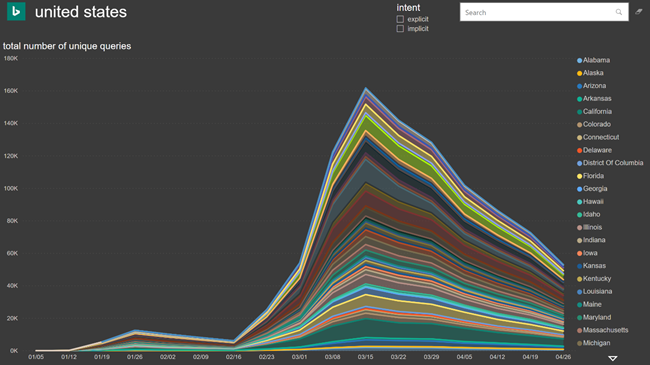

Our analysis shows that the number of such unique queries is highly correlated with total query volume (0.99), indicating rapid growth in query volume beginning in mid-February and peaking in mid-March. In this view, we can also use the search box to filter queries based on their content, for example all queries, in this dataset, containing the word “cruise”:

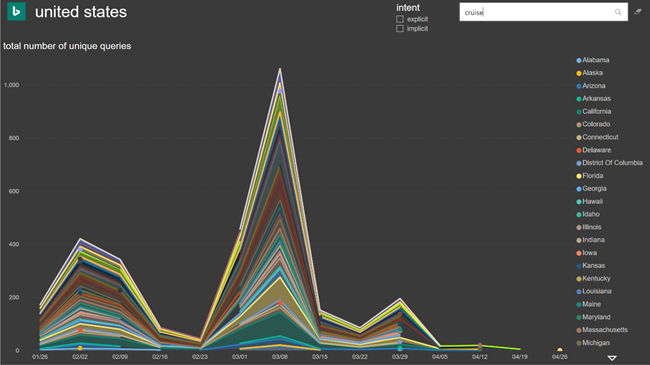

Here we see three spikes in interest: early February, early March, and early April. To learn more about the content of the queries driving these peaks, we can switch to a different view showing the top queries by day:

Now we can see that the February peak relates to the top query “japan cruise ship quarantine”, the March peak relates to “carnival cruise coronavirus”, and the April peak relates to renewed interest in “cruise ship coronavirus”. This view also captures daily spikes in specific queries, such as “honolulu cruise ships coronavirus” appearing as a large blue column on March 19. Note also how top queries like “cruise ship quarantine” and “carnival cruise cancellations 2020” reflect implicit coronavirus intents, in that they are intimately connected with coronavirus without referencing it explicitly. We can filter this view to examine the evolving concerns of US Bing users through March and April, as shown below:

We see that in our dataset, “hand sanitizer” is the top ranked concern in early March and retains a stable level of popularity overall, but is overtaken by other queries over time. These include “stimulus checks for 2020” on March 18, “sba disaster loans” on March 23, “easter 2020” on March 24, “how to make a face mask” on April 3, “crocs for healthcare workers” on April 20, and “remdesivir” on April 29. This clearly shows how search queries track what is in the news and on top of people’s minds about the pandemic.

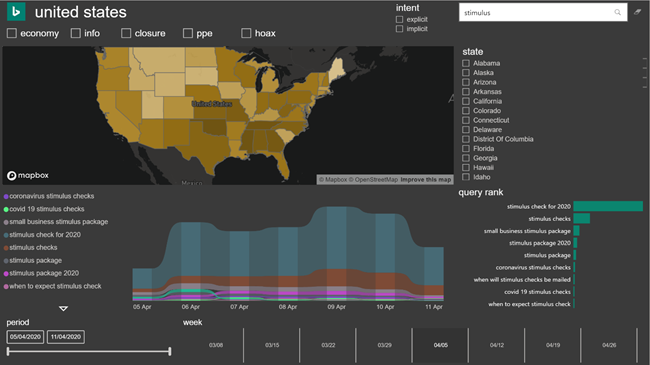

We can analyze queries by geography as well as time. For the week of April 4, we can see that there is nationwide interest in “stimulus”, but queries containing “stimulus” only reach maximum overall popularity in Oklahoma and Mississippi:

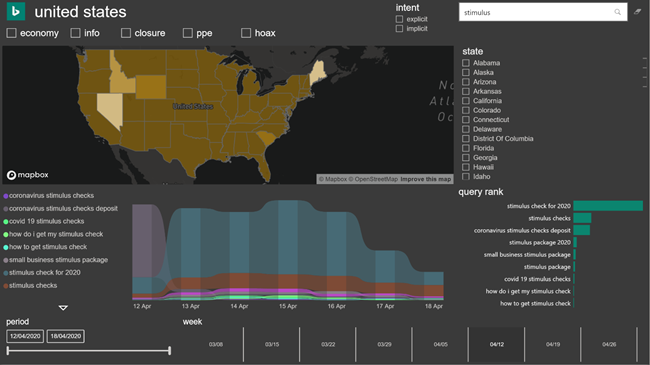

In contrast, for the following week of April 12, queries containing “stimulus” reach maximum popularity in all states except Nevada, Idaho, Wyoming, Kentucky, South Carolina, and Maine:

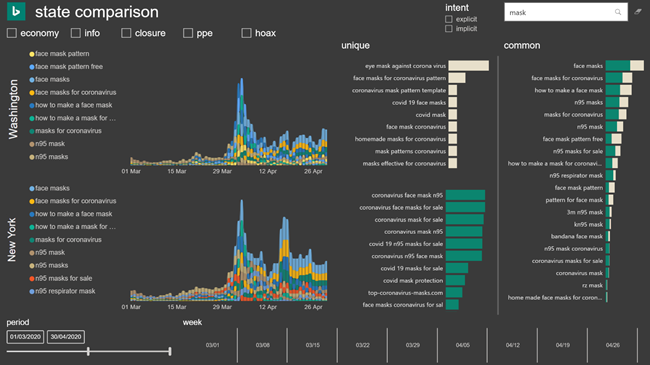

We can also use the dataset to make comparisons between states, countries, and topics. For example, here is a comparison of Washington state and New York state from March, this time for all queries containing the term “mask”:

We can see that the two states share a broadly similar time course and have many common queries in Coronavirus intent dataset, including the top shared query “face masks”. However, we can also observe subtle differences, such as Washington state having more unique queries and a greater share of common queries relating to mask patterns and the creation of homemade face masks, and New York state showing the opposing bias towards n95 masks and face masks for sale.

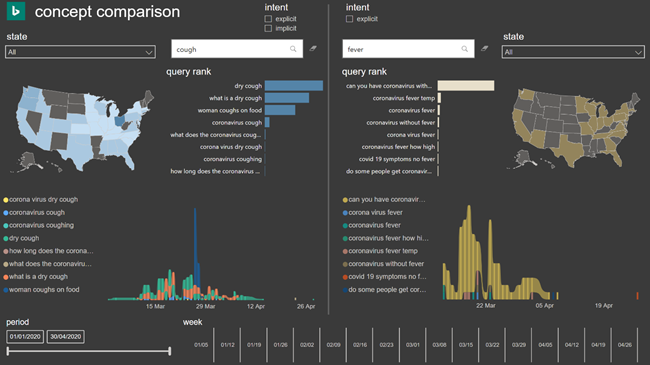

Here is another comparison, this time of symptom-related queries across the US for the month of March:

We see that queries containing “cough” and “fever” both made an initial jump in popularity on March 12, maintained high query levels for the following two weeks, then dissipated in early April. The greatest interest in either symptom came on March 26 in relation to the news story “woman coughs on food”. The most popular fever-related query by far was also “can you have coronavirus without fever?”

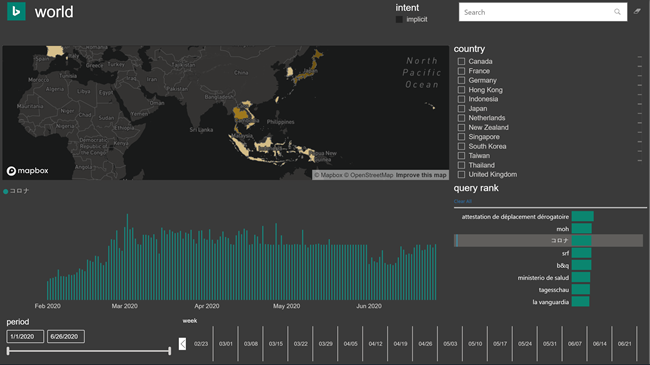

Finally, if we look at worldwide queries, we can notice that the implicit intent detection also captures relevant queries in other languages. For example, here we can see the Japanese transliteration of “corona” (“コロナ”) featuring as a top implicit query not just from Japan, but from Japanese speakers around the world:

Comparing trends in Bing Covid-19 queries to other data streams

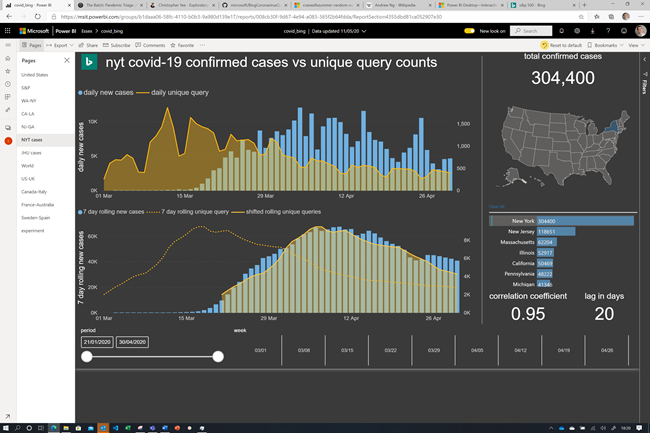

In addition to comparing the relative popularity and types of queries within the dataset, we can also use Power BI to compare the number of daily unique queries against other time series potentially related to aspects of the Covid-19 crisis.

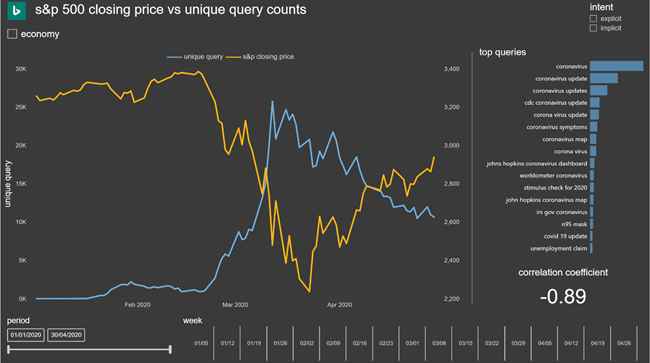

When we compare daily unique Covid-19 queries to the closing price of the S&P 500 index, we observed a strong inverse correlation (-0.89), with “fear” as a potential common cause. While the initial drop in the index preceded the rise in unique queries by several days, the recovery in April lagged the falling query count by almost two weeks. It will be interesting to see the relationship between these two datasets as we move further into summer and if we see another increase in confirmed cases.

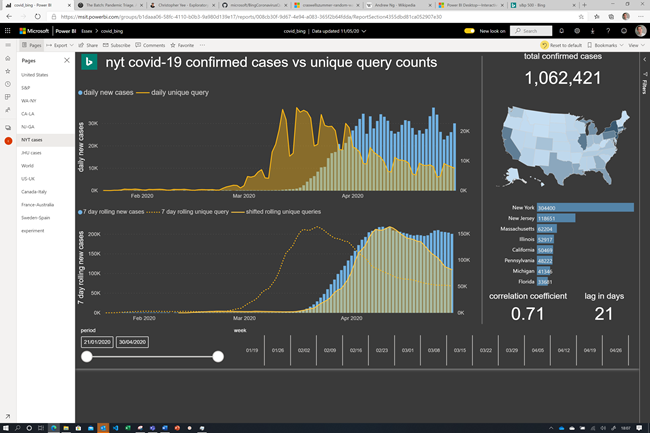

Similarly, when we compare unique query counts from the dataset to the number of confirmed cases using the New York Times dataset, we observe that the shape of the confirmed cases distribution roughly follows that of the daily query count, only shifted. This relationship becomes clearer when we smooth both curves using a 7-day rolling sum and translate the query curve to maximize the correlation. Across all states, we see an average such correlation of 0.71 and lag of 21 days from daily unique queries to daily new cases:

This correlation is especially striking for some states, including New York:

While correlation does not imply causation, the degree of correlation and the broad similarly of lag observed across states (potentially related to the length of the incubation period) is the kind of visual insight that may be investigated further over the course of the pandemic.

Conclusion

By publishing the Bing Coronavirus query set, we have tried to bridge at least part of the information gap that exists between our need to understand the public experience of the Coronavirus pandemic and the public availability of datasets that yield insights into this experience. As with any dataset, however, users of the data need to consider potential sources of bias, for example the relative popularity of the Bing search engine in different geographic regions, as well as the relative populations of those regions. It is always advisable to account for such factors before generating insights.

Since the pandemic does not appear to be going away in the near future, the evolving data will continue to reveal insights into what is ‘top of mind’ for different populations over time. It is our sincere hope that this dataset can provide an important signal as we deal with the impact of Coronavirus and the need for reliable information that it creates. After all, we are all in this together. The Bing search dataset for Coronavirus intent is already available on GitHub, meaning anyone with data science or business intelligence skills can begin exploring the data today. We are actively seeking feedback on the dataset at BingCoronaVirusTeam@microsoft.com, and would especially love to hear from anyone who has used the dataset to support Covid-19 response efforts.